Background

There seems to be two main camps in this violent debate between Internal Combustion Vehicles (ICE) and Electric Vehicles (EVs) For convenience, we’ll refer to the first group as The Tesla Fanbois, and the second group as The Never EVs. I’m not in either camp. I’m just a regular dude, a long-time open source software guy, who keeps ridiculous maintenance logs, writes blogs, does analysis and works on cars, motorcycles and bicycles. I believe in the power of sharing and collaboration, so I’ll tackle this article using the maintenance log from my daily driver, and I’ll provide commentary along the way for major costs which I think were unique. This commentary is developed from countless debates I’ve had with Never EVers and Tesla Fanbois.

My daily driver is a 2008 Jeep Grand Cherokee which I bought in October, 2013 with 130,000 miles on it. At the time of this writing (May 2024) this vehicle is 16 years old, I’ve owned it for 11 of those years and it has 236,000 miles. That should make this a great example because it’s had plenty of maintenance on it, and I’ve tracked it all here in this maintenance log so you can analyze it yourself. Some of the maintenance I did myself, but the vast majority I paid shops to do. There are three primary places I took the vehicle: 1. Dominic’s Auto 2. Fred Martin Superstore (Jeep Dealer) 3. Valvoline for most fluid changes. None of these places is particularly cheap. In fact, I’d say they’re on the more expensive side, but I valued convenience over budget.

I should also note that I’ve driven this vehicle 116,000 miles myself, and towed it another 10,000 miles behind an RV all over the United States. Towing a vehicle like this definitely has an impact on the tires, brakes, and suspension components, but it wasn’t a huge percentage of the mileage. Also, I don’t baby my vehicles. I service them well, but I’m not particularly kind to them. I drive at 100mph, I rev the motor to red line, I brake hard, I drive around corners aggressively from time to time. I enjoy driving, and I drive my vehicles. I even drove the RV towing the Jeep at 80mph out West. I also modify my vehicles, often tuning the motor and transmission (both the Jeep and the RV pictured are tuned), I replaced the brakes with red calipers and better pads, etc. I look for performance where I can because I like to drive.

Analysis

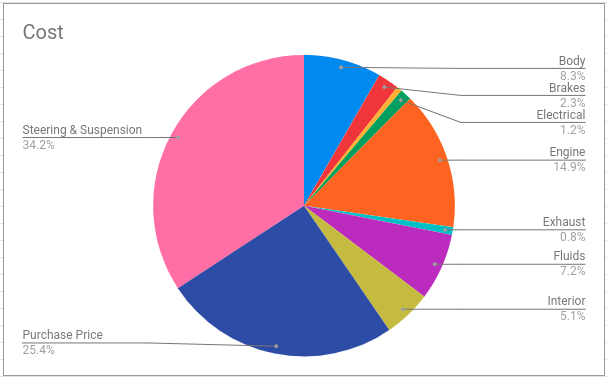

First, let’s analyze the cost by subsystem within the vehicle. From the pie chart, you can quickly see that there are two very large expenses, the Purchase Price ($8900) and Steering & Suspension ($12,001.20). That means the vast majority of the maintenance cost was with suspension components which includes tires, wheels, shocks, struts, wheel bearings, control arms, ball joints, tie-rod ends, sway bar bushings, sway bar end-links, and the rack & pinion system for steering. This makes perfect sense because the most entropy is generated by the ground you’re vehicle drives over. It wears out tires, and shakes the entire chassis. It also aligns with the maintenance logs for other vehicles I’ve owned.

The next biggest cost was indeed with the engine ($5200). I included things like starter motors and 02 sensors because EVs wouldn’t have these. That said, I need to point out that the vast majority of this cost was a single job when I had the timing chain done at 216,000 miles ($3418.82). The dealership urged me to essentially rebuild the top of the motor while they had it apart to do the timing chain. They may have pushed me into a more expensive repair than I needed, and I might have found a cheaper shop, but I can say that the motor purrs like a kitten at 236,000 miles. I suspect this motor will go well past 300,000 miles as it is now.

Next after the engine was the Body ($2920.65). I try to keep my daily driver really nice so that I won’t be annoyed by it, because I know that’s key to keeping it as long as possible. I want it to last as long as possible because that’s the cheapest way to subsidize daily personal transportation, but also because it’s good for the environment. In particular, my vehicle was in a hail storm, and the insurance company wouldn’t cover it. They claimed that the type of damage wasn’t consistent with hail, even though I had a video of 1″ hail hitting it. Sadly, this could happen with any car, EV or ICE. It’s a wash.

As many EV advocates claim, Fluids were indeed the next biggest cost ($2522.29). These costs are likely much higher than for the average owner. First, I bought this vehicle with 130,000 miles and I had no idea what fluids had been changed, so I had them change every single fluid: Coolant, Power Steering, Differentials, Transfer Case, Oil, Transmission Fluid, etc. Second, I believe that proactively changing fluids prevents major issues down the road, and I think my maintenance log generally shows that. Also note that many 4×4 EVs have differentials, coolant and transfer cases and might need strange and much more expensive fluids at high mileage.

The next largest cost was spent on the Interior of the vehicle ($1796.60). This included things like really nice floor mats, and trunk mats, but the biggest cost was actually replacing the Evaporator for the air conditioning ($1355.25). I attribute this to the vibrations and strain placed on a vehicle with $186,000 miles on it. I’m pretty sure that an EV would have the exact same problem with a heat pump, which is also susceptible to vibrations in the chassis.

The rest of the costs are really just odds and ends and easily subsidized over time on a vehicle with so many miles on it, but I do want to address Brakes ($801.79). I hear a lot of hemming and hawing about the cost of brakes, and it’s just not as expensive as the EV advocates say. I drove this vehicle 110,000 miles, and pulled it another 10,000 miles behind an RV (which can wear out the brakes and tires quite a bit). Brakes just aren’t a big expense unless you’re racing a vehicle (which I’ve done), in which case, brakes and tires become extremely expensive.

Conclusion

If you’re leasing a new car every 2-3 years, none of this matters. If you’re buying a new car every 3-5 years, none of this matters. Maintenance just isn’t going to matter to you. All new cars are ridiculously reliable compared to my 1961 Plymouth Valiant. Mostly, you should just buy what you like. You’re going to pay a premium for that comfort, with insurance costs, finance costs, etc but who cares. If that’s what makes you happy, and you can afford it, do it! But, if you would prefer to spend that budget on other expensive hobbies, like I do, then the total cost of ownership probably does matter to you. Based on my maintenance logs and costs, I think there’s an opportunity to save money on engine repairs and fluid changes with EVs, but there are some serious caveats.

The first caveat is that chassis and suspension costs are the biggest cost in any vehicle over a long enough time period. If you keep an EV for 10 years and drive 100,000-200,000 miles, suspension costs are going to be a big chunk of the cost. Worse, it’s not just the cost, it’s the headache. Suspension issues involve, clunks, and rattles, and vibrations. They’re hard to troubleshoot, and often require taking your vehicle back to the shop multiple times. With the wait times at Tesla service centers, lack of aftermarket parts and repair facilities, expensive OEM parts, and reputation for having suspension problems in general, I suspect that suspension parts are going to be even more expensive, not less.

The second caveat is the cost of replacing a battery because Tesla and other vendors don’t repair the batteries, they only replace them, and the cost is quite expensive. Batteries simply do not fail that often under normal conditions, but if they do, they’re easily more expensive than the combined costs of the engine and fluids in my Jeep. In the future, I believe local repair shops will open up, similar to cell phone repair shops, and they’ll be able to repair individual cells within an EV battery. But, vendors like Tesla will need to do more to design their cars to be repairable, and value Right to Repair. Tesla isn’t a fan of swappable batteries, so this is going to remain a challenge. This NPR article supports my analysis: What’s sending first-generation electric cars to an early grave

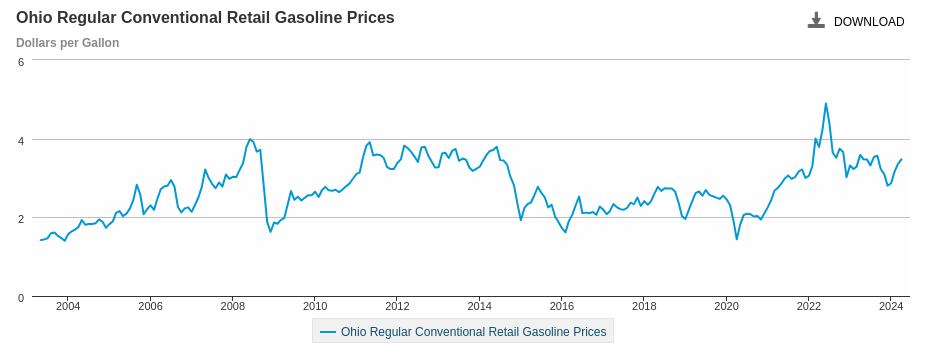

The counter argument is the cost of fuel versus electricity. In Ohio, where I live, we have middle of the pack electricity costs, and the math simply doesn’t pen out. Doing a quick calculation on my Jeep: I’ve driven 116,000 miles at approximately 13 miles per gallon, at approximately $3.00 a gallon, which is approximately $26,769 in fuel costs. Using a Rivian as the closest thing I can think of to compare my Jeep to, it costs 18 cents per mile with all home charging, which comes to $20,880. If we stop here, the EV looks pretty good.

But that’s not the real world. In the real world, most of those 116,000 miles are on the highway traveling between cities. I’ve used this vehicle while on vacation, and when I was in sales, covering neighboring states for about 2.5 years.

To be more realistic, let’s say that 30% of these miles were using fast charging while on the open road. That gives us 81,200 miles with home charging at $14,616 and 34,800 miles fast charging on the road at approximately three times the cost of electricity for $18,792. This brings our total electricity cost up to $33,408. That’s $6,639 more than my Jeep. The fuel cost argument doesn’t seem to hold up based on my math.

The next thing we have to think about is the cost of insurance. Insurance costs on Teslas and other EVs are quite expensive, partially because they’re almost all late model vehicles, and partially because when they crash the expensive battery can be damaged (remember Tesla doesn’t repair them, only replaces them). I haven’t even taken this into account, because my vehicle is so old it will win insurance costs hands down.

Finally, let’s think about total cost of ownership. Not just in dollars, but also in landfill and environmental impact. These environmental impacts are externalities, but I consider them important, and so do most EV owners. My vehicle cost me $35,481.94 to drive for 11 years, and I can probably sell it for $5000-7000 for a total cost of $30,481. That’s pretty darn good. But, it also makes environmental sense, to prevent global warming. When old vehicles like mine get sold, they don’t actually go into a landfill or recycled, they get sold in developing countries located in places like Africa where the vehicle is used for years and years running worse and worse and with much of the pollution abatement equipment likely torn off (something I used to do when I younger and couldn’t afford repairs).

There are nearly 8 billion people on this planet, yet there are only 1.2 billion ICE cars on the road. I’ve ridden motorcycles all over the planet, and I can tell you first hand that people are doing the craziest things with motorcycles, from carrying rolls of carpet, to packing their wife and 2-3 kids on the back (and front). That means there’s about 6.9 billion people left that would like the convenience and safety for their families offered by the protection of glass and steel around them, especially when it rains, or in the hot sun. These trade-in ICE cars aren’t going in landfills, unless they just can’t run anymore. That’s why I plan to drive my Jeep a bit longer, hopefully until it actually gets recycled for parts.

I love the look of the Hyundai Ioniq 5, and I love how fast EVs are (I test drove a Tesla in 2020 and loved the incredible power), but the math still doesn’t pencil out. If you want one because you want to send market signals, or because you want a super fast car, or because you want people to think you’re cool, do it! I support you. But, surely you’re still paying a premium, and I’m pretty darn skeptical that buying an old Honda Civic wouldn’t actually be better for the environment.

The Trials Motorcycle Anomaly

I’m not super excited about replacing my Jeep with an EV yet, but there’s one place where I *am* super excited about EVs. Trials motorcycles.

The EV range to weight challenge is still a HUGE blocker for adventure bikes, road motorcycles, and enduro bikes, but for Motocross bikes it’s getting close (see Stark Varg), and with trials motorcycles, I think it’s a no-brainer. With the Electric Motion (EM) ePure Trials motorcycle, I think it’s essentially better in almost every way possible!

I ride BMX bikes, dirt jumpers (small mountain bikes used for jumps and tricks), mountain bikes (for riding in the woods and on single track), enduros (gas motorcycles for riding similar trails), and adventure bikes (for riding long distance on gravel roads and single track). I also love riding trials (see Tony Bou), essentially riding around doing small tricks all over the place. While I’m not nearly as good as Tony Bou, and I’ve only ever ridden trials on bicycles, I want to get better, and want to do it on a motorcycle.

A trials motorcycle is beautiful for several reasons. It’s a much smaller and lighter motorcycle, typically weighing around 150lbs instead of 200-250 like typical dirt bikes, or 350-550lbs like typical adventure bikes. This makes it a lot easier to learn on, and a lot less dangerous. A smaller bike has a much smaller chance of crushing you and breaking bones, etc. These trials motorcycles have 21″ front wheels and 18″ back wheels (like bigger bikes) and are long enough and big enough to give you skills that transfer to bigger bikes.

There’s just one problem….Maintenance and noise.

Enter the EM ePure electric trials motorcycle. It’s small and light like a normal trials motorcycle, but has essentially zero maintenance, and makes less noise so that my neighbors won’t want to murder me when I practice drills in the driveway! Range isn’t an issue with trials motorcycles, because I typically only ride 7-10 miles in a multi-hour session, and it can charge in my garage. It even has a hydraulic clutch, and idles the electric motor so that you can crawl around using only the clutch, building up transferable skills when you get back on enduros and adventure bikes (something I like to do).

There’s just one big problem. They cost like $11,000 for the one I want. Sigh 🙂

EVs could be easier to maintain, but I’d guess a new crate motor and fuel tank is still cheaper than a new series of EV batteries. I’m with you on the motorcycles